Breadcrumb

- Essential Partners

- Our Impact

- News and Notes

- No, We Won't Calm Down: Emotion and Reason in Dialogue?

No, We Won't Calm Down: Emotion and Reason in Dialogue?

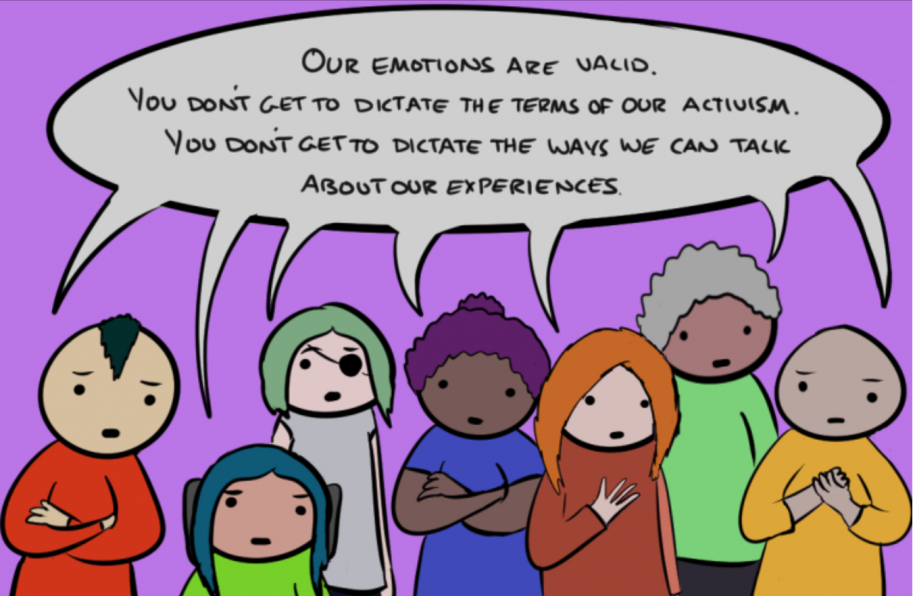

A recent cartoon on digital platform Everyday Feminism stimulated a lot of questions among Essential Partners staff. Entitled “No, We Won’t Calm Down-Tone Policing is Just Another Way to Protect Privilege,” it raised important issues about power, privilege, the apparent contrast between reason and emotion, and the roles of advocacy and dialogue.

Tone policing

The protagonist, Robot Hugs, talks about how tone policing allows privileged people to define the terms of a conversation about oppression and how this “hinges on the idea that emotion and reason cannot coexist---that reasonable discussions cannot involve emotions.” It further asserts that this allows privileged people to regain control of a conversation that is making them uncomfortable and thereby avoid the discomfort caused by being exposed to the very real emotional fallout of oppression and discrimination.”

Our dialogue work frequently focuses on polarized and extremely controversial topics that touch on issues of power and privilege. We see “tone policing” as something to be avoided; we value people’s bringing their feelings into dialogue. That is one reason we talk with participants beforehand: to offer guidance about how they can speak in ways that are more likely to be heard, and how to listen with resilience. The communication agreements that participants commit to beforehand are ones that they have jointly drafted and found acceptable to support their purpose in having a deeper, more authentic conversation.

Power and privilege

The cartoon raises challenging and important questions about power and privilege that surface frequently in the course of our work. In fact, many partisans (on whatever side of a controversial issue) see advocacy and dialogue as mutually exclusive and cite issues of privilege and power imbalance as reasons it should be avoided. As Robot Hugs continues, “these conversations aren’t meant to be comfortable. We are discussing real, dangerous, structural things that make lives worse for entire groups of people. If it makes you feel uncomfortable, the thing to do isn’t to try to get us to talk about it differently--the thing to do is to help us stop it from happening.”Why there may still be a need for dialogue

There are, however, many occasions when people on different sides of important issues feel the need to sit down and talk together. They may be tired of conflict or violence or may see the potential benefit to their community of such a conversation. Our work in Montana was initiated because pro and anti-open carry advocates decided that it was important to try to understand each other’s perspectives, to strengthen their communities and keep them safe. In Nigeria, we worked with Muslims and Christians who wanted to address sporadic outbreaks of violence between their communities.

Bottom line, there are times when people experience the need to listen to one another, as a first step toward building relationships and trust. If such efforts succeed, people may be interested in attempting to work together to address problems, when neither group can solve the problem on their own.

Shared purpose, shared power

A dialogue is a conversation that participants enter with the clear and shared purpose of mutual understanding. They have also had an opportunity to contribute to how they want to be together. They contribute ideas that will promote this purpose, so they are the ones who are actively participating in designing the structure and communication agreements, rather than someone who is more privileged or powerful “imposing” them. They have agreed to focus on certain questions, to limit the time of responding, and to respond in ways that enhance learning and connection. We are aware that everyone is not always interested in such conversations and they may not be possible in certain circumstances.

The power of agreements

The agreements are co-created by all participants so that those who are “privileged” hold the same power as all others. Agreements can be negotiated throughout the process, so that if something is not working the opportunity to fix it exists. In dialogue, the purpose of the conversation is a mutual understanding. We know that when people are having difficult conversations around polarizing issues, it is helpful to create a space for effective communication. Hard work! In order to create a safe space, specifically one that does not induce a flight, fight or freeze response, a person has to feel safe.

Avoiding fight, flight or freeze

A part of our brain is watching for danger and may prevent us from being capable of having a constructive conversation when we most need it. When there’s a lot at stake and we feel under attack, the brain and central nervous system release hormones designed to keep us hyper-vigilant, with physiological (racing heart rate, cold, sweaty palms, etc.) and psychological effects. Our capacity to think and reflect shuts down as we prepare for fight, flight or freeze. A conversation with highly emotional responses, however, justified, can trigger this reactive response. A structured, voluntary conversation, however, creates a sense of safety and wellbeing so that participants can focus on the narratives and not the fear that emerges because of feeling threatened.

One example of this dynamic occurred a number of years ago, in which issues of power imbalances and privilege caused collaborative work to run aground and precipitated a request for our assistance. The Massachusetts Department of Mental Health had received a three-year federal grant to reduce the use of seclusion and restraint in its psychiatric hospitals. DMH formed a Steering Committee, which included people with lived experience of psychiatric illness, family members and advocates; mental health clinicians, hospital directors, and staff.

Although all the participants shared a common purpose, the enterprise foundered within its first six months, as Steering Committee members experienced massive frustrations, with many voicing the sense of not feeling seen or heard by others. People with lived experience spoke powerfully of their sense that DMH staff were unwilling to hear their experience of having been traumatized by the seclusion and restraint orders that psychiatric hospital staff had initiated. In response to voicing their concerns, the message they heard back was that they needed to speak differently so that the (more powerful) DMH staff would not feel attacked. Many of the clinicians felt guilty and misunderstood, seen as one-dimensional and complained of being attacked verbally when they attempted to engage or empathize. From their perspective, there was a power imbalance in terms of the “moral power of the victim.”

Freedom through structure

One of our first tasks was to help them figure out how both sides could express themselves clearly and powerfully, in ways that invited thoughtful listening, rather than resistance and shutting down. How could the issues of power and privilege be addressed in a way that would allow them to resume their work together? We began by meeting with each group separately and helping them think through their priorities and their purpose in coming together. It soon became evident that there were significant differences within each group.

We encouraged a candid discussion that focused on helping them identify the kinds of behaviors and commitments that would support their purpose. As participants explored their own feelings and experiences within each group, they engaged energetically with each other. As facilitators, we did not impose “ground rules” but allowed these to emerge from the group after thorough discussion.

When the two groups came together one of the first items of conversation was the negotiation of these ground rules. This was accomplished quickly and it successfully provided the kind of “safe-enough” space within which participants were able to have a more fruitful conversation that led to their getting back on track.

Purpose first; no policing later

To return to Robot Hugs, one of the underlying assumptions that we noted was the lack of clarity in identifying the purpose of the conversation. Robot Hugs expressed the belief that sometimes conversations are not just for moving toward solutions but they can also be for exploring situations, letting off steam, finding community and feeling less alone. The cartoon suggested that those conducting the “tone policing” had very different purposes for the conversation, namely to retain their power and privilege and avoid feeling uncomfortable.

One thing that we emphasize in our work is the importance of purpose. If the purpose of a conversation is clear and shared, then developing shared commitments of how people want to be together can help support that purpose. If the participants have very different purposes for the conversation, these differing purposes frequently manifest behaviorally and interfere with task accomplishment. If the purpose involves mutual learning and understanding, differences of power and privilege can usually be directly addressed and successfully negotiated. This kind of direct and open conversation focused on mutual learning and understanding, can lay the foundation for collaborative action to create more fairness and justice.

Robot Hugs rightly complains that the more powerful people sometimes want to make the rules of the game, to impose their views on how the conversation should be held. In our work, communicating with participants beforehand helps to address issues of purpose, conducive behaviors, and commitments. Groups might, for example, talk about sharing airtime, listening with resilience, and other kinds of behaviors that would help support their purpose.

Emotion and reason are not enemies. We want people to bring their feelings and their passions into the room when they engage in dialogue, but not to be overwhelmed by them. And we want to help them to think about how they can express these in ways that invite listening with an open heart and speaking in ways that invite receptivity.